Exploring Dartmoor National Park

Discover Tors, Granite Formations, and Hidden Heritage with Emma Cunis, founder of Dartmoor’s Daughter.

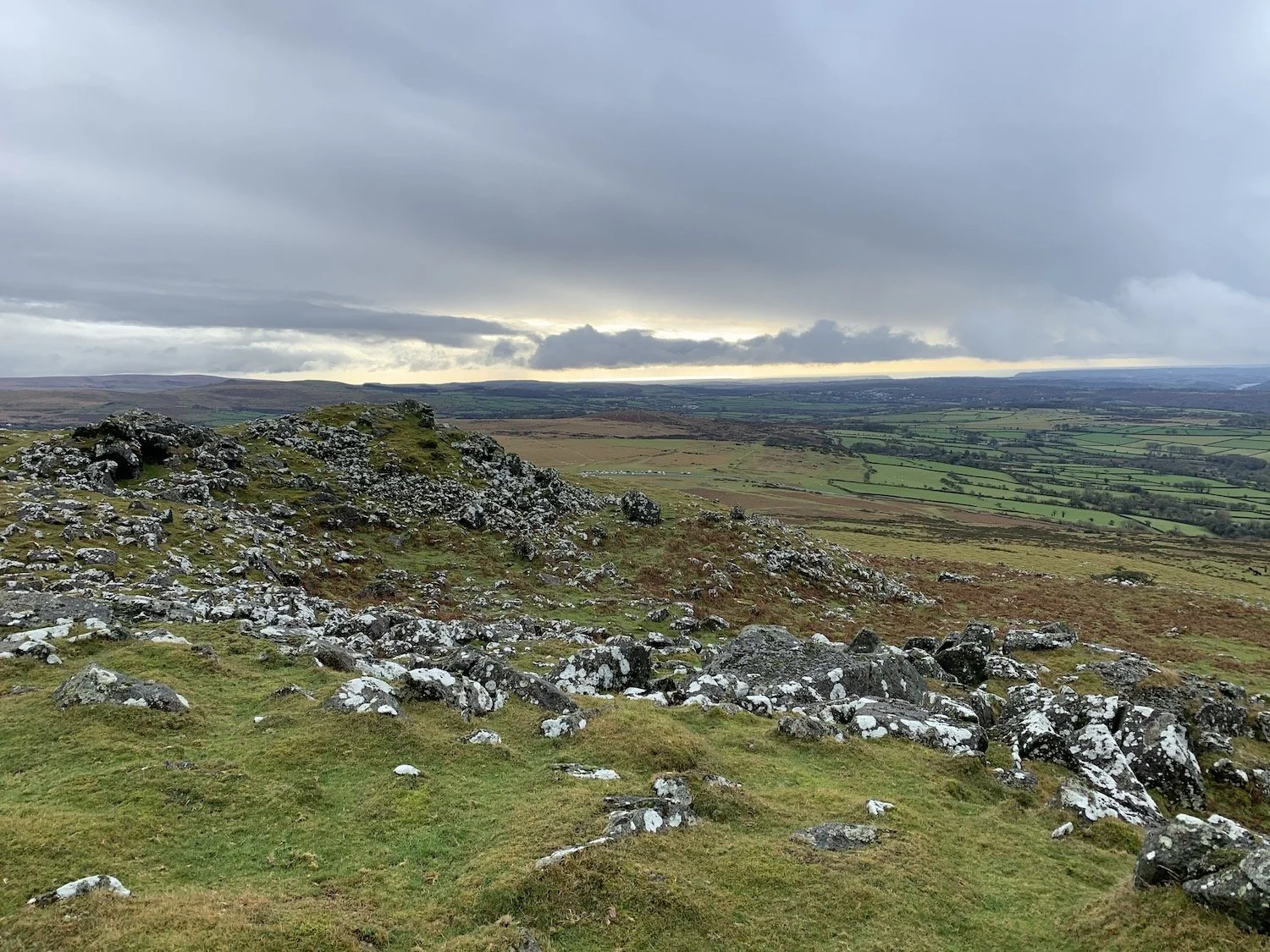

Great Staple Tor

Dartmoor National Park is the largest open space in southern England - 368 square miles of high and scenic moorland; lush wooded valleys; fascinating wildlife; and meandering copper-gold coloured rivers. There is so much to explore, enjoy, and learn about. Unlike national parks in the US for example, Dartmoor is a living, working landscape and it is free to visit. I live here, and so do thousands of others. We have a rich cultural, farming, and industrial heritage that has shaped the land and traditions that we know and love today.

Dartmoor’s heathland is underpinned by an enormous granite batholith that is the remains of the Amorican mountain range that finished forming around 290 million years ago. The freeze and thaw action of successive ice ages, compounded by strong winds and slightly acidic rain, weathered away the former overlying rocks to reveal the majestic granite tors of today. I like to think that we are walking amongst the bones of old mountains.

What is a ‘Tor’?

The word ‘Tor’ comes from an old Celtic word ‘twr’ meaning tower, and these extraordinary natural formations can be found on the top or side of hills, or deep in the valley floors. Each is distinctive, with differing sizes, shapes, and names. Each tor has a name, which often tells us the story of the place, particularly if it’s pronounced using the Dartmoor dialect. For example, ‘Hey’ Tor means ‘high’; ‘Cas Tor’ might reveal the old lair of a big cat; and ‘Eagle Rock’ is the old haunt of the golden eagle’ (sadly no longer here). This rich blend of landscape, language, and history are crucial in shaping our understanding of this exquisite land and it’s inhabitants.

Tors are wonderful places to explore for both adults and children. Many are easily accessible with a short walk from a car park such as ‘Combestone Tor’, ‘Kestor Rocks’, ‘Haytor’, ‘Hound Tor,’ ‘Bench Tor’, ‘Cox Tor’, ‘Sharp Tor’ near ‘Bel Tor Corner’, ‘Yar Tor’, ‘Belstone Tor’, ‘Bellever Tor’ or ‘Leather Tor’. Others require good navigational skills to visit as they are far into the wild moor and it’s important to have good equipment (weather changes can be rapid and forecasts are often unreliable), and local knowledge to avoid treacherous ground (you might want to consider hiring a guide).

Some of the tors have formed into unusual shapes – if you look closely you might be able to see their resemblance to faces, animals, or mythical creatures. ‘Bowerman’s Nose’ and ‘Hound Tor’ are said to be all that is left behind of John Bowerman (‘Bowman’) who was out hunting with his pack of dogs when he was turned to stone for upsetting the magical moonlight rites of a witches coven in the nearby woodland. Of this statuesque granite stack, the poet NT Carrington wrote

“On the very edge

Of the vast moorland, startling every eye,

A shape enormous rises! High it towers

Above the hill’s bold brow, and seen from far,

Assumes the human form; a granite god, –

To whom in days long flown, the suppliant knee

In trembling homage bowed. The hamlets near

Have legends rude connected with the spot,

(Wild swept by every wind) on which he stands

The giant of the Moor!”

King Arthur and the devil were reputed to have hurled mighty stone quoits at each other and, in so doing, formed ‘Helstone’ and ‘Blackingstone Rock’. ‘Crockern Tor ‘is the home of ‘Old Crockern’, the old god or spirit of Dartmoor, whose head and face is supposedly profiled in the rocks there. Near the centre of the moor, ‘Crockern Tor’ was the important outdoors meeting place of the medieval ‘Stannary Parliament’ who met to determine laws and resolve issues for the tin-mining industry. ‘Vixen Tor’, likely to have been the home of a fox, has been said to resemble the Sphinx in Egypt, or from another angle a man carrying his wife on his back! It is also reputedly the home of ‘Vixana’ a witch who lured lone travellers to their death by falling into a dangerous bog.

You can discover little caves in some tors such as at ‘Greator Rocks’ and the ‘Piskies Cave’ at ‘Sheepstor’. The King of the Piskies was said to live under ‘Pew Tor’. And if you walk up to the centre of Pew Tor with it’s stunning 360 degree views, you can take a seat in the giant ‘Druid’s Chair’.

Emma Cunis at Bowerman’s Nose

The Druid’s Chair at Pew Tor

A Sacred History

If we look to indigenous people around the world to understand more about our prehistoric history and culture, we can see that natural features such as mountains, rivers, and springs are often considered sacred. And so there is a possibility that Dartmoor tors were similarly revered. Dartmoor has the highest concentration of prehistoric stone rows in Britain, as well as 15 stone circles (smaller versions of the more famous ‘Stonehenge’), standing stones, and burial chambers (more about these ‘ceremonial complexes’ in a future article). However, there are many structures built around the tors that pre-date these standalone monuments. Large cairns or burial chambers are a common feature of hill tops. And recent research revealed that the large ruinous walls surrounding ‘White Tor/Whittor’ and ‘Dewerstone Rock’ are not Iron Age Hill Forts as previously thought but in fact ‘Neolithic Tor Enclosures’. It’s unclear what these large and deliberate demarcations were for – archaeologists think perhaps for excarnation; as special living areas (although there is no water source inside here today); or areas of worship. There’s so much to learn about and discover on Dartmoor – everyday is a ‘school day’ here!

There are also several ‘Propped Stones’ and rocks deliberately moved to change their angle on top of or nearby tors. ‘Eastern Tor’ is a good example of this. It’s not known whether this is an ancient practice or modern but it’s interesting to speculate on their purpose as well as age.

And there are quite a number of ‘Cairn-covered Tors’ where thousands of small rocks have been deliberately placed around the tor to completely cover it. This is quite a feat when you see the size of some of the tors! They were originally assumed to be funerary monuments that are thousands of years old but not all cairns have evidence of burials inside. Examples of ‘Cairn-covered Tors’ include ‘Cox Tor’, ‘Corndon’, ‘Ugborough Beacon’, and ‘Shell Top’. They remain a mystery.

The Dartmoor Victorian archaeologists assumed that everything had a druidic association so they posited that the large ‘rock-basin’ situated on top of ‘Kestor’ was dug out by and used by the Druids for their magical and sacrificial rites. The rock-basin on ‘Great Mis Tor’ is called the ‘Devil’s frying-pan’ as he was said to be frying the souls of sinners sent to hell – a nice cautionary tale to encourage us all to behave well on Dartmoor! In fact, these stone vessels are naturally formed by wind and rain over millions of years but still the magic of the stories persists.

Cox Tor - a cairn enclosed Tor

A cairn covered Tor

Section of ‘Neolithic Tor Enclosure’ at Dewerstone Rock

Kestor Rock Basin

Dartmoor’s Granite

As well as providing durable building materials for houses and field systems for thousands of years (the remains of Bronze Age settlements can be seen across much of the moor), Dartmoor granite has also supplied some of the grandest buildings beyond it’s boundaries. Technically complex systems were created to quarry the granite; transport it via Dartmoor Pony pulled carts along tramways to canals and then onward to large ocean-going ships; and supply food, shelter, and schooling for the families of men working the quarries far from home. In London alone, Dartmoor granite helped to build the British Museum, Buckingham Palace, Nelson’s Column, old London Bridge (which is now in Lake Havasu City in Arizona).

Haytor Granite Tramway

Dartmoor Granite Tramway

Wheelwright’s Stone under Barn Hill

What is a Dartmoor Letterbox?

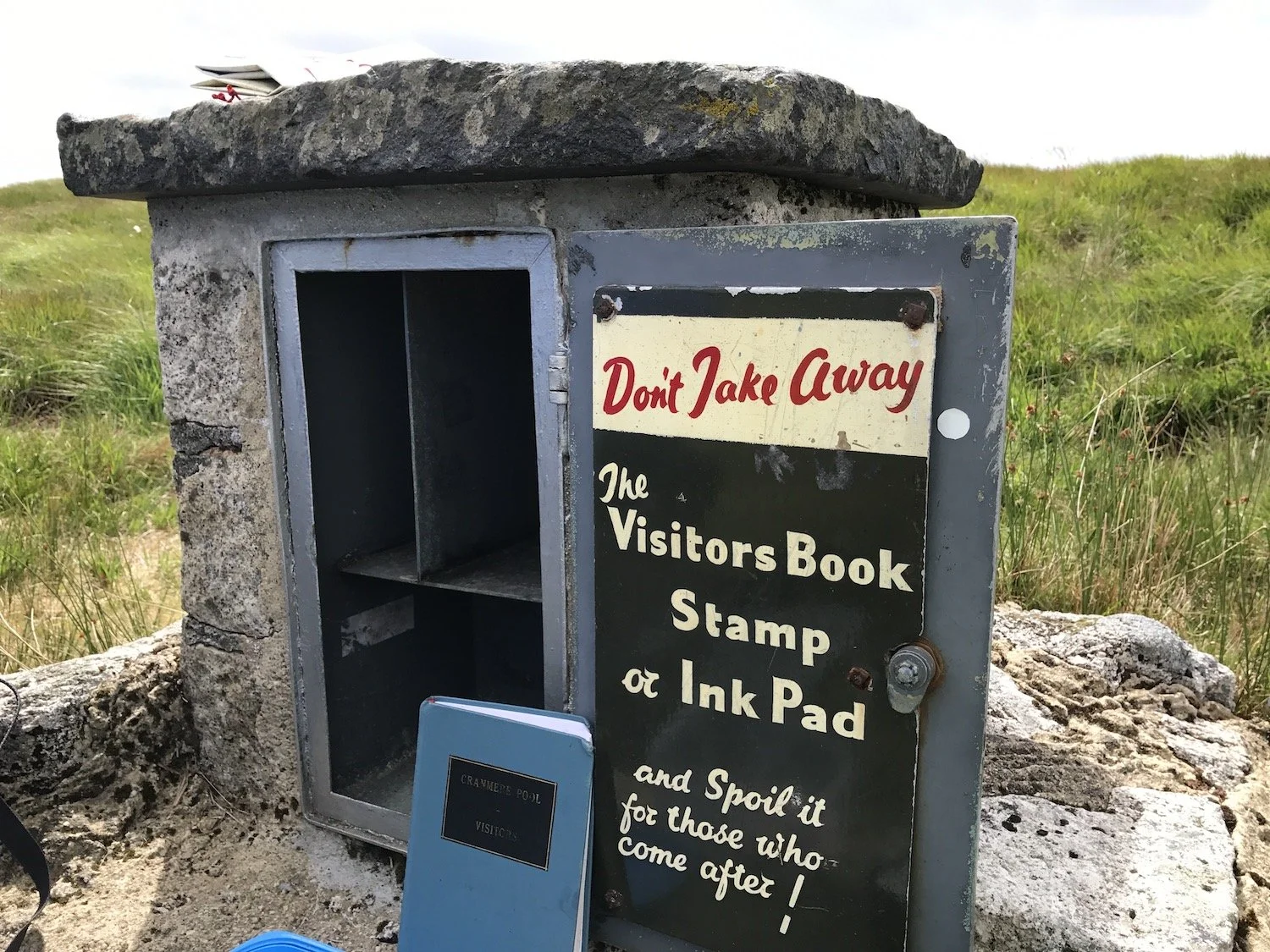

If you get the chance to visit Dartmoor and it’s glorious tors, you might be lucky enough to find a ‘Letterbox’. These little boxes are hidden in rocky crevices and there is usually a notebook to write a message in, and an ink stamp to leave your mark. This tradition was started by a Dartmoor Guide in 1854 and, although it has gone through various iterations, there is usually at least one letterbox at most tors on Dartmoor. We like to think Dartmoor Letterboxing was the humble beginnings of worldwide Geocaching!

Cranmere Pool Letterbox

Looking for ‘Letterboxes’ at Belstone Tor

Visit Dartmoor

Dartmoor is beautiful all year round, with something different to see in every season. There are plenty of facilities here including visitor centres, traditional pubs, and splendid hotels with excellent food, pretty B&BS, and villages with shops, cafes, galleries, and handmade crafts. So we hope you come to visit us soon.

Article originally published on the We Are England website.